What's in a Name?: Czech Naming Customs

Monday was my name day, and not a single one of you got me a present.

Name days, for those who aren't familiar, are days in which we celebrate people with specific names. Why should we do that? Well, like many weird traditions, the answers lies with the Church.

In the Middle Ages, the concept of celebrating birthdays, a venerable tradition, was seen as pagan--because, well, it was. Many pre-Christian peoples celebrated birthdays, often quite lavishly. That was unacceptable to the "everything pagan is bad and must be eliminated or co-opted" mentality of the medieval church, so they did a bit of both. They strongly discouraged the celebration of birthdays, but in their place, they offered the name day. For those who aren't familiar, the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches have a calendar of saints' feast days. Essentially every day of the calendar year is the feast day of some saint--usually many saints. The most famous example is likely February 14th: the feast day of St. Valentine. So, the Church decided that all Valentines would have a special day on February 14th--like a birthday, but with more religious significance, and without that nasty pagan history. And thus, the name day was born.

Over the years, with the decline of the power of the Church, the preponderance of saints to assign days to, and the rise of European nation states in the place of vast empires, the specific practices and calendars have gotten more localized. But many European countries still celebrate name days in some way, including the Czech Republic.

Czech name day celebrations are usually quite small. Family members and close friends might give small gifts like flowers or chocolates. Friends or family members who share a name (an extremely common occurrence) might celebrate together and make it more of a party, but the name day celebration is definitely less important than the birthday celebration.

The existence of a calendar of name days gives rise to the question: what if your name isn't on the calendar? Barack Obama doesn't get a name day in the Czech Republic, alas. When naming their children, Czech parents still generally stick to the names on the calendar, not the least because, while it is not illegal to name your Czech child Barack, it can generally create problems. There is a semi-official list of approved names (essentially the names on the calendar), and parents who wish to name their child something else have to get special permission. The law states that, as long as the name is used as a name somewhere in the world and isn't deragatory, the name is supposed to be approved. However, Czech bureaucracy being what it is, most parents still choose the traditional names.

According to a poorly sourced Wikipedia article, only about 250 names appear more than 500 times in the Czech Republic. Regardless of the exact statistics, this is born out by everyday experience. Some names become more or less popular over time, but no name that isn't on the calendar is anywhere near the top of the charts in terms of popularity.

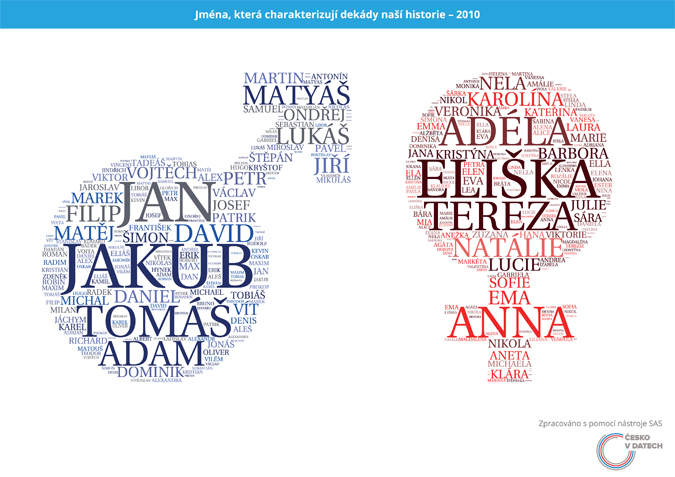

The word clouds show the most popular boys and girls names in the 2010s, with Jakub (Jacob/James) overtaking Jan (John) for the top spot for the first time in several decades. Eliška (Elise, related to Elizabeth) is the most popular girls name, with Anna close behind. The most popular names are so common that once you have a group of 15-20 people, it is almost certain that multiple people will share the same first name.

One way of distinguishing between all the Jans and Jakubs is to use diminutives or pet names, with different Czechs opting to use different versions of their names as they age or in different situations. The most common of these is probably Honza for Jan, but a Jakub at work may be Kuba to his friends and Kubíček to his grandmother. I've also noticed a trend for younger Czechs to go by an English version of their name in certain situations: so Kateřina becomes Kate and Michal, Michael. Whether this is an attempt to make it easier for their teachers to pronounce their names or just because they feel English names sound more natural in English sentences is unclear.

As the chart indicates, Czech names are entirely gender-specific. This extends to last names, as well, meaning that women will ususally have different last names from their fathers (if they're unmarried) or husbands (if they're married). There are a few different ways of doing this based on the origin of the last name, but suffice it to say that Mr. Navrátil's tennis playing daughter becomes Martina Navrátilová. Indeed, because Czech names reflect Czech grammar (with two genders), even foreign last names often get the -ova ending, with the recent British Prime Minister being called Mayova in the Czech press.

Plus, because Czech is a declined languaged -- meaning that the nouns in a sentence change based on what role they're serving -- each Czech name, both first and last, has up to 14 different forms. In addition to the mascline and feminine forms (Navrátil/Navrátilová), there are grammatical case endings for each name. So, the name Erik, which exists in Czech but isn't terribly popular, can become Erikovi, Erikem, Eriku, among other forms, depending on whether you''re doing something to Erik, or with Erik, etc.

All of these rules and conventions, ultimately stemming from the language and its grammar, create a certain uniformity and familiarity--a cultural cohesion. Howver, it also means the system is ill-equipped to handle of the growing modern appreciation of the complexities and nuances of things like gender identity. In Czech, everyone name--and therefore every person--is either male or female, period, and that fact is known since birth. It remains to be seen how adpatable this system will be to people who fall outside that traditional dichotomy.

Comments

Post a Comment